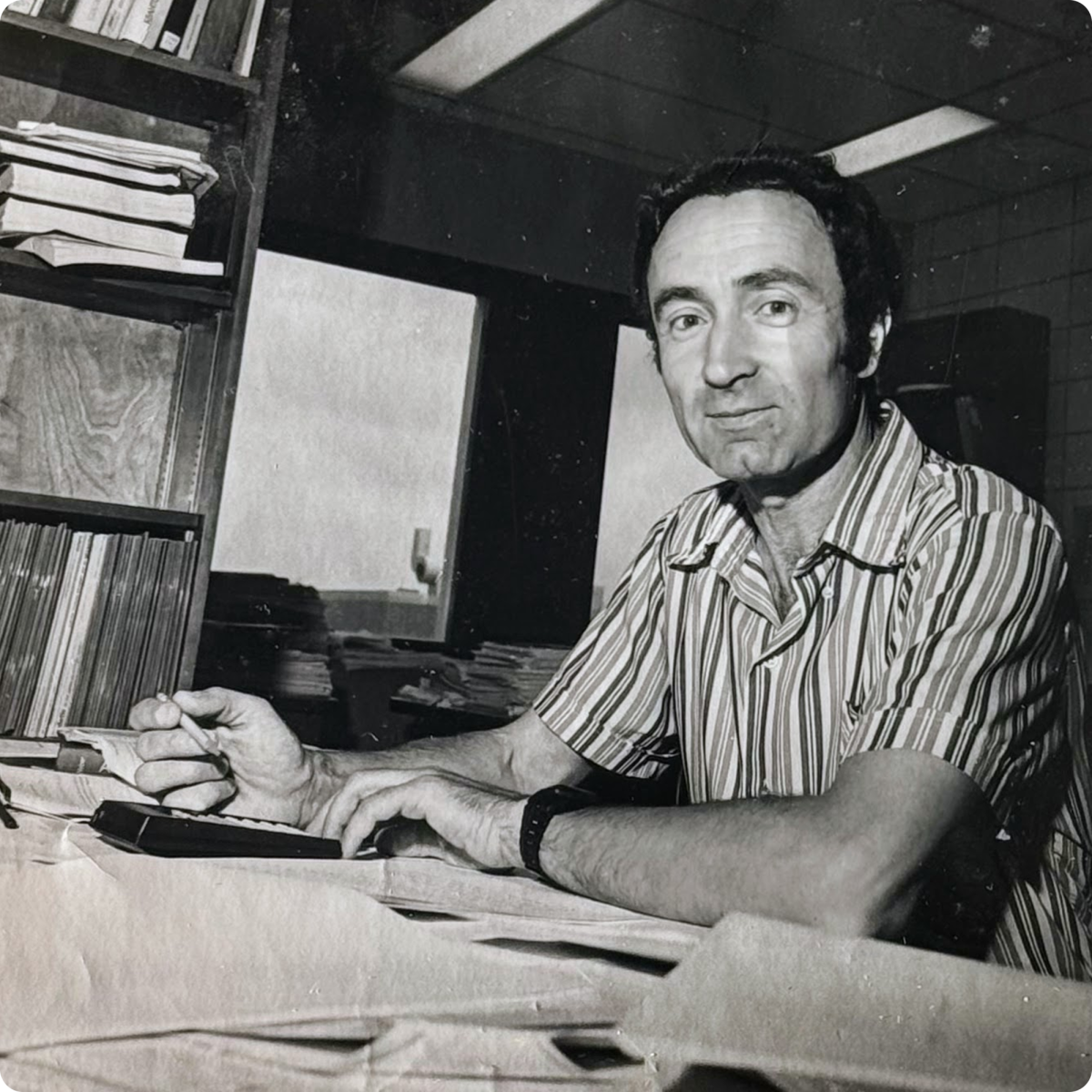

Physicist Vladimir Kogan dedicated his life to advancing research and his family. Vladimir Kogan’s exploration extended beyond intellectual life, finding inspiration in the outdoors and embracing adventures of all forms.

Some who knew Vladimir Kogan would describe him as courageous, which was evident in his willingness to distribute literature banned by the Soviet government during his time in the USSR, an endeavor that reflected his commitment to personal freedom.

“At some point, he was distributing this illegal literature… novels that were banned, and he would retype them on a typewriter with carbon copy paper and distribute them to different people just to read,” Ruslan Prozorov, professor and senior physicist at Iowa State, said. “That was quite courageous because he could be jailed for that.”

His passing at the age of 90 marks the end of a career that contributed to theoretical physics and the understanding of vortex dynamics in superconductors.

Prozorov, a long-time colleague of Vladimir Kogan, recalled their relationship.

“We sort of clicked right away,” Prozorov said. “We started collaborating closely, publishing many papers together over almost 20 years. He would write equations, and I would run numerical simulations. He was extremely active, coming to work every day, discussing things and staying engaged with the research until the very end.”

Beyond academia, Vladimir Kogan was an outdoorsman. He and his wife, whom he met while hiking, shared a lifelong love for nature, often traveling across the United States and various countries.

“My parents were always traveling to national parks throughout the West, especially places like Zion and Bryce and Rocky Mountain National Park,” Uri Kogan, his son, said. “In 2002, my dad and I hiked across the Grand Canyon from the North to the South Rim. That was a 24-mile hike with a vertical mile climb at the end–he was 68, and still in incredible shape.”

Uri Kogan described his memories of father.

“I definitely remember laying in bed and, like my kids do now, I didn’t want to go to bed, so I’d ask him questions. ‘Why is the sky blue?’ or ‘How do airplanes fly?’ And he would always take the time to explain, kicking off a little lecture on the fundamental principles of physics,” Uri Kogan said.

Vladimir Kogan was described as a man of deep integrity. While soft-spoken in social settings, he was unwavering in his beliefs.

Uri Kogan described him as social with the people he knew well. He wasn’t interested in small talk, but if there was something of substance to discuss physics, history or politics, he would be very animated and engaged.

His theoretical knowledge helped scientists better understand the behavior of vortices within superconducting materials, which in turn played a role in advancing the development of superconducting magnets and other technologies.

Vladimir Kogan’s research was highly regarded, leading to numerous publications and prestigious recognitions. At 24, Vladimir Kogan failed the second entrance exam for Moscow’s Landau Institute with Alexei Abrikosov, who would later win a Nobel Prize for physics.

At a conference over 50 years later, Vladimir Kogan met with Abrikosov again, and a few years thereafter, won the Abrikosov Prize for his contributions to the field of superconductivity.

Ruslan described Vladimir Kogan as humble, noting that he never sought recognition or nominated himself for anything. Vladimir Kogan was always surprised and delighted when others referenced his papers.

Vladimir Kogan’s early years were shaped by war and political turmoil. He faced significant obstacles, including discrimination due to his Jewish heritage.

Growing up during World War II, he relocated to various Russian cities and villages for protection, including Nizhny Novgorod and Chine’evo. A few years later, he made it back to his hometown of Smolensk, where only one room of his family home remained and German night bombings continued.

Vladimir Kogan then survived the 1947 Soviet famine, at age 13, which killed two million people.

According to Uri Kogan, despite earning a silver medal at 18, which should have secured admission into a Moscow University, he instead faced intense interviews due to the rising antisemitism and KGB-enforced quotas that severely limited Jewish students, particularly in physics.

He pursued his undergraduate education in Smolensk and later graduate studies in Moscow.

Barriers made it difficult for him to continue, leading him to work as a tutor and lecturer for a decade before obtaining his Ph.D. in Israel after emigrating in the 1970s.

After earning his Ph.D., he conducted postdoctoral research in Germany before moving to Ames, Iowa, in 1980, where he became a research scientist at Ames Laboratory.

Vladimir Kogan came to work in Ames initially for postdoctoral research with John R. Clem, another renowned theorist in vortex physics. Clem was the last graduate student of John Bardeen, who received two Nobel Prizes in Physics.

Vladimir Kogan retired at 84, but still collaborated and published research papers until his passing.